From the autobiography of Fr Ambrose Agius

From the autobiography of Fr Ambrose Agius

Monk of Downside and Ealing

Parish Priest of Radstock, Whitehaven, Liverpool

Chapter 9: Whitehaven.

1932-1934

Last Parish Priest from Downside Abbey before handing over to Belmont Abbey

My first outside Mission was Whitehaven, in Cumberland. In accordance with the casual system then in vogue, I had no training in bookkeeping, pastoral theology or diocesan regulations, and I had never served on a mission away from Downside.

Typically, Abbot Chapman called me aside between his conference and Vespers, and announced my new post. There were three other priests there, Fr Walter Mackey, who used to teach us English (when Ambrose was at Downside School 1900-07) and was then running the parish magazine, Fr Maurus van Thiel, an indefatigable worker, and Fr Oswald Sumner, on loan from Belmont.

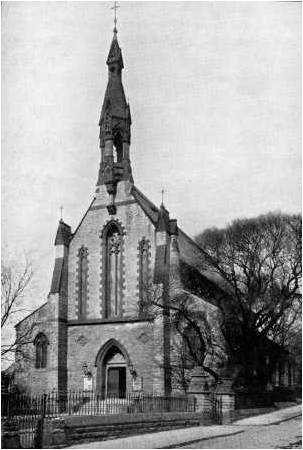

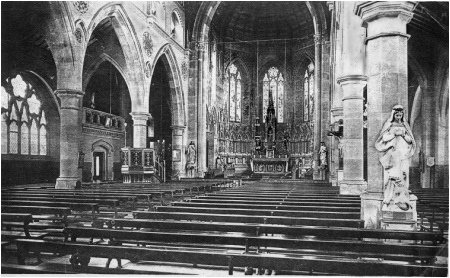

We had touching farewells at Radstock, where I now had many friends, and took the long journey through Bristol and past Lancaster and, in cold weather, into an enchanting land of deep sea bays and mountains. In the last few miles the guard of the train, a parishioner, came to chat and pass the time away pleasantly. At the small station Fr Michael Caffrey was waiting in his car. After half a mile we drove into Coach Road, past the satisfactory Pugin church to the inconsiderable but adequate presbytery a few yards away.

———————-

The site of the church has a history. The Lonsdale family dominated Whitehaven and owned the coal mines, whose refuse polluted the beaches. On one occasion, the parish priest acted as mediator in a crippling strike and negotiated a settlement. The grateful owner offered a piece of plate as recompense, but this was useless to the priest, who asked instead for a site on which to build a church. This was given, with all necessary building materials. Coach Road, along which in olden times coaches ran from the harbour inland, was then on the very edge of the town, but later developments surrounded it with houses. The now valuable property could then have been bought for a song, as at Ealing and on many of our missions. Still, there was room for boys’ and girls’ schools for nearly 100 children, presbytery, parish hall and church. And for residents near the waterfront, there was the chapel in Quay Street elementary school. There a partition divided the altar from the classrooms, and on Sundays it was drawn back, and the worshippers squatted uncomfortably on the infants’ benches.

Confessions were heard on Saturdays, as well as at St Begh’s in Coach Road. I used to hear from 4-5 pm have tea with a Catholic family nearby, and get back to St Begh’s for another hour and a half Confessions. Fr Mackey, who relieved me, would have his tea there just before me. He was particular about tea-leaves in his cups so he acquired a silver strainer and presented it to the family “for services rendered”. Gratefully they accepted it, and put it in a glass-fronted cabinet. Slightly embarrassed, Fr Mackey had to convey his wish to have it used for his own tea.

Fr van Thiel had charge of the temporary church at Kells, about three miles from St Begh’s, on a high cliff, from which magnificent views were obtainable to the Isle of Man out to sea, Scotland to the north, and the Fells of the Lake District inland. He used to walk (I used to wonder how) up fasting on Sunday morning, get the stove going, hear Confessions, preach, attend a meeting, sing a Missa Cantata, attend to parish business and walk back about midday for his first meal. When we three came in for dinner, he would be at the toast and marmalade stage of his breakfast. Without a break he resumed operations and had a full Sunday dinner. Then he would walk back to Kells for Sunday School and evening service, with an apple in his pocket, and need no more sustenance till next day.

The schools were just behind my sitting-room. The children wore “clogs”, shoes with wooden brass-tipped soles, and the clatter of their feet on the stone stairs was impressive. Tom Clancy, headmaster of the boys’ school,was a devout man, a good disciplinarian and a fine teacher and a good friend. Every Saturday morning (they worked till midday) he went around every class urging frequent communion. The result was that Communions on Sundays took the priest twenty minutes to distribute, for we had eight Masses on Sundays. Fr van Thiel was at Kells, I was at the other two outlying chapels, and Quay Street had to be served, so no one was available to help give Communion at St Begh’s. The straits I was in when ‘flu laid us all low, except Fr Ward, can be imagined.

The outlying Chapels were at Moresby Park and Parton. The former, small but devotional, was already there, on a housing estate about three miles from Whitehaven. The little congregation here was singularly united and devout. Parton, once a harbour for the Romans in their “combined operations” drive into Scotland, was just a cluster of houses on a rocky shore, with a building project housing about 300 people farther inshore. I went over one day with Fr Ward, and we found 70 Catholics more or less unregistered. So I looked around and finally discovered a disused Hall formerly belonging to some defunct Benefit Society, in quite fair condition, with main room and stage and a couple of smaller rooms beyond. I bought this for £120 ! (We were a depressed area in the worst years of the “slump”).

Local volunteers fell upon the place, and mended and cleaned and scrubbed and saved; and before long we had a charming little chapel. Our Bishop, Arthur Thomas Pearson, who had taught me at Downside, came over with me one day and administered Confirmation, to the joy and enthusiasm of the people.

The homely people made me welcome in their houses. Sometimes I would take the opportunity to snatch a swim. When a storm blew up, the women used to stand on the beach and gather the coal washed up by the waves from the outcrop below the surface. For at Whitehaven the coal beds ran under the sea, and so did the mines.

———————-

The whole North-West coast, from Millom to Carlisle, with the exception of Millom, was served by Benedictines, mostly in Pugin-built churches which were inexpensive (£6000) but roomy, shapely and satisfying. The theological conferences were the occasion for fraternal reunions, both in the discussions and in the subsequent dinner. In addition, the parish priests of the three bigger parishes, Clayton Green, Whitehaven and Workington, took it in turns to stage a Christmas Dinner each year, and these were friendly and pleasant. On one occasion I had provided, as an after-dinner novelty, a “banana”, really a firework laden with gifts. I duly lit the fuse, and the thing exploded against the ceiling with a bang, showering watch chains and similar hardware on our unsuspecting heads.

The whole West Cumberland area, during the “depression”, was abjectly poor. In some villages 10% of the people had been out of work for ten years. The old iron ore mines, probably dating from Tudor times, had been neglected in favour of foreign markets. The coalmines, chief source of employment, were shut down; tho’ a kindly Scottish Combine opened them up for a short while. The foreign firms, driven to England by the war, and the profitable nuclear plants were still undreamt of. So finances were on the hand-to-mouth scale; and tho’ we kept our heads above water, Downside wasn’t particularly interested as we were supposed to be giving up the parish to the secular clergy. Indeed, on the way back from Lourdes, I went over the details of handing over to my successor, Fr Eaton.

But our Benedictine bishop was reluctant for us to surrender this historic mission. It went back to the beginning of 1700, and in my baptism register the Godparents still had their own name “Gossips”. In those days, the single priest still included the Isle of Man in his parish, and sailed over “at Easter or thereabouts” to bring the few Catholics up to date. So Bishop Pearson asked me one day what to reply to Rome asking his views on surrendering the mission. I said “Do you want us to give it up?” and he said “No”. So I outlined an answer for him, and the reply came back “Let the Benedictines stay in the parish where they have laboured so fruitfully”.

Now it is run by Belmont Abbey; and is no longer a depressed area. The miners donate a small contribution, which the clerk at the pit obligingly stops out of their wages, and there are many new factories and the nuclear establishment are close by. Some Benedictines anyhow must be glad it wasn’t given up.

———————-

Near the boys’ school, but totally different in character, was the girls’ school. The Headmistress, Sister Mary, was a disciplinarian, ambitious and efficient. The top girls were several grades ahead of the normal school rating. But results were obtained by a harshness to children and teachers which I found intolerable. Even the local Education Authorities were all scared of her. I found her one day condemning to the deepest rigours of hell a mother who had sent her daughter to a school procession wearing an off-white headscarf. One day, a teacher burst into my room in tears, saying she could never go back under Sister Mary. Exercising a power which I assumed for the occasion, without warrant I am now sure, I gave her a month’s leave of absence on full pay. And the local authority consented! But I felt that to give way and accept the tyranny would be detrimental to myself and any future parish priest. So I refused to be bossed.

One girl had won a scholarship, but Sister Mary, who had had a tussle with her parents, refused to put her name on the Honours’ Board. During the summer holidays, I had the board removed and amended. There was, of course, an explosion. Sister Mary wrote to the Catholic Education Council, and part of the advice she received was that, since I had interfered with her authority, any question of misdemeanour should be handed over to me to deal with. Soon such a case came up; collective disobedience and impudence. I scared the girls so effectively that Sister Mary paid me a grudging compliment, and sent me no more cases.

One night, the situation was piquant. Sister Mary and another Sister went to the school after dark and saw, as they thought, a man with a torch already in the school. They came to me for escort. Blissfully (without showing it) I went across, and discovered that what they had seen was the reflection of their own torch on some glass inside. Before I left, I went to Sister and begged her pardon for the occasions when I had upset her. Even then she wanted me to confess I had been wrong. But I had not, and could not say so. Then, a wonderful sight, she corked up her fiery spirit and asked my forgiveness in turn.

The Head teacher at Quay Street was a rotund, motherly nun, who clucked over her charges like a hen over her chicks. They had a charming Christmas party, when the whole school sat with lighted candles and sang carols. She was always at me to have the partitions between the classrooms installed. I demurred, not having the money. Then came an ultimatum from the Education Office; they had promised to build a school on the top of Kells Hill, but first I must tidy up Quay Street.

In my innocence, I proceeded to carry this out. Since the mission was due to be handed over, no council at Downside would have approved of £2000 being spent on Quay St. But it happened that a Nurse Wilson had left a large sum of money, on trust, to help indigent girls. After consultation with the Trustees, I obtained a loan from them, at interest, and paid the Contractor without borrowing. Probably quite irregular, but it worked. Kells is now a separate parish, as the congregation increased rapidly.

During the building of the new school some hitch occurred, and I went up to London with the architect. Two young men had been deputed to interview and instruct us; but when I asked their own education and teaching experience, it turned out that one at least had only been to a village school, and neither had done any teaching. Quite irrelevant, of course, but I exploded and we won.

———————-

The climate at Whitehaven could be formidable. A storm could blow in off the sea at St Bees Head, blow up the valley and meet, as its first obstacle, our church in Coach Road. The original bell spire had to be removed for that reason. One of my men who was up there just before said he felt it swaying twelve inches in the wind.

I was several times quite ill there. In my first winter a severe flu virus laid me low, and two of the other priests as well. The following winter I had arthritis in my knee. I remember lying in bed, with a plaster bandage on, being tormented by the boys’ choir and the Silver Band both practising at the same time in the school just across the yard. The Dr Logan came and carried me in his car to a Nursing Home up the hill; a fortnight of pleasant ease and gradual recovery. After that, I went to my family in Malta to convalesce, seeing my mother for the last time before she died in 1935.

———————-

We had two Missions given by Redemptorists during my stay. The good priest in charge was of enormous bulk but very effective. I am afraid I was, on both occasions, convalescent and unable to give them much relaxation. But I expect they forgave me.

Two great names in old St Begh’s were Fathers Gregory and Bernard Murphy. When I waited on them as a novice at Downside when they came in for their annual Retreat, they seemed like beings from another world. One day one of them decided that it was time to take the accumulated pennies down to the bank. But their weight was too much for the old cab that had been hired, and the floor gave way, with the venerable father running with elbows propped on the window-sills, trying to attract the driver’s attention. Years later, the floor of the Guest Room at St Begh’s gave way when Archbishop Downey came to attend the Annual Rally of the CYMS. He pushed his bed slightly, and one leg went right through the floor. One of the priests came in at that moment, but the only comment he could offer was “It’s gone right through the floor”, which was sufficiently obvious.

———————-

At Whitehaven I had happy relations with non-Catholic individuals and Societies. An example is the British Legion. At Downside I helped to organise the Legion over the whole of Somerset, wrote about it in the south-western papers, and conferred with the leaders in London and at annual rallies. In Cumberland the Legion was widespread but disorganised. I managed to link up with the leaders in Carlisle, and also locally helped to establish a new H.Q. and to recruit members. On Armistice Day I conducted the service at the Cenotaph in uniform, and organised an ex-service men’s parade ending up at St Begh’s with a special service. When I left, as the men wished for a souvenir of my association, they arranged for a special portrait to be taken and mounted in the Legion H.Q. All my life I have had the happiness of being accepted by men, of all faiths or none, as one of themselves.

On the devotional side, it was my happiness to organise a Lourdes’ party from the north-west. The first time we set out in a small party, with a few more from Workington, and arrived at Preston late on Sunday night to find provision made for the two priests but none for the people. We were therefore delayed some time till a friendly Convent took them all in.

It was a very long journey to Lourdes, 36 hours, but our small Lancastrian pilgrimage was homely and devout. Our engine next morning from Preston bore a large circular board proclaiming our identity. In France, for the sick, we had empty luggage trucks in which we laid the stretchers on trestles, primitive, but airy and unobstructed, with room to visit the sick and hold informal tea-parties. Lourdes was partly empty, and we had processions, took charge of public services, and had ample facilities for bathing the sick and ourselves. So the fatigue of the long journey was amply repaid. But it was tiring, and I went into the saloon towards the end of our journey and found everyone asleep in various attitudes, as if suddenly asphyxiated, holding books and even food in their hands. So at three in the morning we came home to Whitehaven. The second year we started in style. The boys’ choir and about 500 people rose very early and attended a sung Mass in St Begh’s. Then we went to Corkickle Station, and found the stationmaster asleep and no sign of a train. We roused him, and discovered that our two coaches were waiting at Bransty, the other station. Presently, summoned by phone, they came through the tunnel, the engine driver surprised at the large crowd awaiting him. So, amid cheers and good wishes, we set off for another pilgrimage. A photo of our arrival at Lourdes shows the utter content on our faces to be again in Our Lady’s favoured spot.

———————-

There was an empty shop in Lowther Street, the main thoroughfare of Whitehaven. I decided to rent it for a month, and put on some Catholic publicity. Each of the four sodalities in the parish, Holy Family, CYMS, Children of Mary and St Therese, took charge for a week. Jimmy Reynolds and his wife came up to stage an opening. The shop was really an Information Centre for the Catholic Faith, so I called it VERITY. The window display had a different colour-scheme each week and was dedicated to a special subject e.g. the Children of Mary portrayed Our Lady, with a blue and white decor. I got Fr Hubert van Zeller, who had been staying with me, to paint suitable designs e.g. archers in action (showing the English bowmen at Crecy fasting because it was Saturday, in honour of Our Lady). The experiment attracted considerable attention.

Before my arrival Fr Mackay had initiated a Parish Magazine, which he handed over to me with a sigh of satisfaction. I edited it for two years. Arthur Fuller, foreman at the Whitehaven News printing works, and the proofreader Mrs Stephenson were most helpful in “putting the magazine to bed” in time. It was a useful contact with the people, and read by many non-Catholics.

By reason of its site on the road to Scotland, Whitehaven was visited by many wandering beggars male and female, besides the local contribution. It became necessary for the various benevolent societies, such as the Personal Service Society (of which I became chairman) and the churches to keep a mutual register in which distribution of money, clothing etc. was tabulated. Even so the “professional beggars” outsmarted us. Then I got in the way of sending them down to a leading Catholic and Saint Vincent de Paul man, Jim Worsley, the two oculist, to be vetted, with authority to dispense alms where needful. This was a practical and successful solution. But even so, I sometimes yielded to supplication, as when an obvious faker came just after we had finished an ample Xmas dinner and I had not the heart to refuse him.

———————-

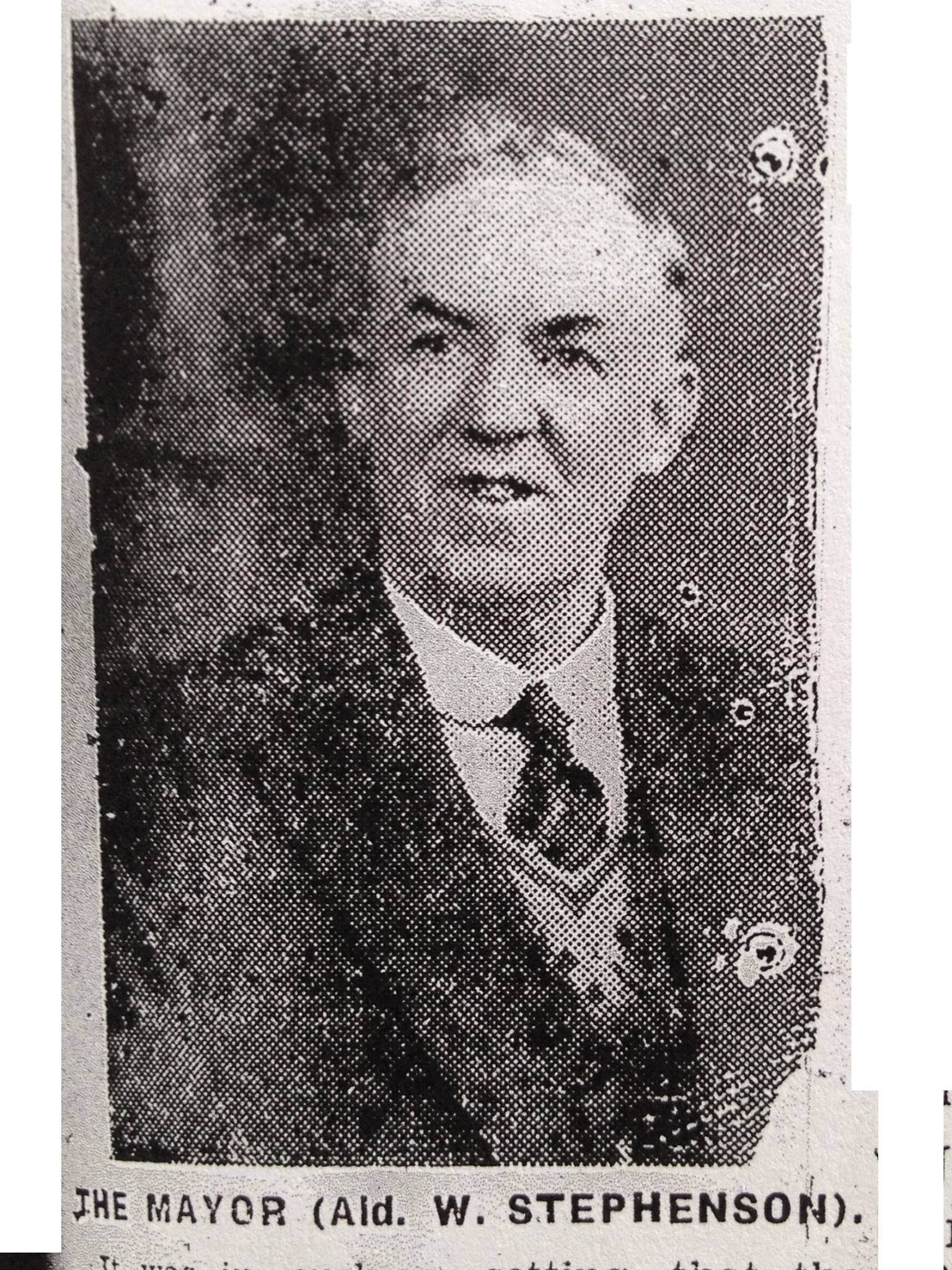

In my first autumn came the Mayor’s election, and for the first time in Whitehaven history a catholic stevedore was returned, Bill Stephenson; a rugged, shrewd Labour man, but a good Catholic. Inevitably, I became the official Mayor’s Chaplain. On the first Sunday therefore after his election, there was the customary procession through the town. This was taken seriously. Besides the Corporation Officials, there walked in full uniform both detachments of Territorials, the Fire Brigade, the Coastguards, the Police, Scouts and Guides. I walked with the Mayor, and it was a long walk. I had already been twice to Moresby (because I had forgotten the Mass hosts the first time) and Parton, fasting, to say Mass as usual on Sundays.

In my first autumn came the Mayor’s election, and for the first time in Whitehaven history a catholic stevedore was returned, Bill Stephenson; a rugged, shrewd Labour man, but a good Catholic. Inevitably, I became the official Mayor’s Chaplain. On the first Sunday therefore after his election, there was the customary procession through the town. This was taken seriously. Besides the Corporation Officials, there walked in full uniform both detachments of Territorials, the Fire Brigade, the Coastguards, the Police, Scouts and Guides. I walked with the Mayor, and it was a long walk. I had already been twice to Moresby (because I had forgotten the Mass hosts the first time) and Parton, fasting, to say Mass as usual on Sundays.

The crowd was too big for St Begh’s, and an overflow meeting was held in the parish hall. The Town Hall had printed the whole Mass, which was unintelligible anyhow to most of those present, being in Latin, and I preached on “Authority Comes from God”. After service, by tradition, we all repaired to the Council Chamber (furnished originally by Lord Lonsdale) and drank hot soup and exchanged congratulations.

On Armistice Day the first embarrassment of a Catholic Mayor arose. Always, hitherto, the Protestant and non-Conformist Ministers had shared a joint service. Now, of course, it had to be a Catholic service, for, as so often in connection with the army and the British Legion, I had to decline participating in a “joint” service. Some Ministers protested vehemently. So I visited the Town Clerk, Mr Bone, who was friendly, and I laid my cards on the table. Either I would conduct a Catholic service at the War Memorial, or they could have their mixed service there, and I would have my Catholic service in St Begh’s. But the Mayor would come to my service. Then they capitulated, and we all went to the War Memorial. My uniform had been freshened up, and Sam Browne and gaiters gleamed, as the troops present noted with approval. Our boys’ choir sang a tune shared with the Protestants, I spoke briefly, and everybody seemed happy.

———————-

Next spring, negotiations went on between the Town Clerk and the Admiralty with respect to the civic visit of one of his Majesty’s battleships to Whitehaven, as well as to various seaside resorts. We were to be favoured with H.M.S. Iron Duke, so old fashioned that there was still an “Admiral’s walk”, a kind of veranda round the stem adjoining the Admiral’s quarters; an indication, incidentally, that British admirals led their ships into battle. But our Iron Duke was a famous ship; Admiral Jellicoe’s flagship in the Battle of Jutland, no less.

On the appointed morning, the stevedore Mayor and his Labour councillors, and I of course, repaired to the harbour where the Admiral’s launch and Flag Lieutenant in full uniform with shining sword and epaulettes were waiting. This rather shook them. A rather silent group was conducted on board, where the Commander and Officers in full dress were waiting. After a little conversation the Mayor opened the ball “Well, lets get cracking (a pause); Lords and Admirals all…”. With a supreme effort the Silent Service kept a straight face, but it says much for their discipline. The previous correspondence must have left an idea in the Mayor’s mind that the Lords of the Admiralty were all visiting in person. Thus the ice was broken, and we lunched happily on board, drinking the King’s health sitting, as is the Navy way.

In the next week the town were hosts to the sailors, football games, excursions, free drinks was the order of the day. The Officers were entertained to dinner. And one day the Commander was conducted to the coalface, two miles out to sea, underneath his own ship floating on the surface above. It was a new experience even for the tough Navy men to be dropped in the cage like a shot down the lift-shaft; but I had been down a mine before, near Downside.Incidentally, the ventilation in these submarine mines is necessarily difficult, and there are still the bodies of some 150 men, many of them Catholics, walled up in an alley poisoned by coal gas.

(Visit of HMS Iron Duke to Whitehaven)

The townspeople also went on board in large numbers on “open house” days, and were duly impressed. On returning at low tide after making our adieux on the last day, the admiral’s launch could not get into the harbour, and we had to transfer to some leaky and precarious rowing boats. But we all thought the visit great fun, although the Protestant clergyman of the church near ours incurred some displeasure by hinting that the “Liberty Boats” from the ship had resulted in the taking of some liberties with the young ladies of the town.

———————-

An admirable institution at Whitehaven was the annual Procession and Fete in aid of the hospital. A large number of dancing troupes and various bands entered the various competitions. As the procession wound through the main streets, it would stop now and again; the bands would strike up, and the dancers give a taste of their quality; a gay and colourful spectacle. We had a young teacher, a Scottish girl, and she had trained a troupe in Highland Dances: they had an inimitable swirl and swing that only a native really understands. The Whitehaven Laundry also had a troupe of professional quality, of which one of our girls was the star.

I had really been sent to Whitehaven to wind up and hand over, but as the Mission had been saved for the Benedictines, it was to Belmont that I resigned my charge, after just two years. I was due to leave in October, but the Town Hall did me the compliment of asking that my departure should be postponed until after the Mayor had entered on his second year of Office, so that I could again conduct “Mayor’s Day” in the friendly atmosphere of the previous year; and so it was done. Then, on a grey November morning, seen off by the schoolmaster and some faithful friends, I took the train to Liverpool. There had been a number of farewell parties, of which that at Parton, in which everyone took part, was perhaps the most touching.

———————-

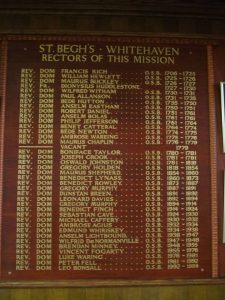

The Rectors Of St Begh’s (Photo – Joseph Ritson)

Thanks also to Joseph Ritson for links to the history of St Begh’s on the parish website:-

History of St Begh’s

Father Gregory Holden

History of the Church in Whitehaven

Benedictines in Whitehaven

Downside Abbey

St Gregory’s Community was founded in Douai , France, in 1607 and sent many monks to to England to come to the aid of Catholics suffering in penal times. After the French Revolution they escaped to England , where Catholics were now tolerated. They first settled in Shropshire and then , in 1814, at Downside in Somerset.

Many mission parishes were run by the monks of St Gregory and other communities such as St Laurence’s Ampleforth. One such was Whitehaven started in 1706 with Francis Rich coming over from Douai. Gregory Holden, in 1818, is reckoned to be the first parish priest to come from Downside and Ambrose Agius the last, 115 years later.