Tancred, the thirteenth child of Edward and Maria Concetta Agius, was born at Belsize Park Gardens in the spring of 1890. He received his early education at St Mary’s, St. Leonards-

In the autumn of 1913 Tancred stayed for a month at Maria-

In September 1915 Tancred was ordained to the priesthood and in April 1917 took up an appointment as Chaplain to the Forces (4th Class), based with the 21st Artillery of the BEF. He served on the Western Front for a year – his battles including Polygon Wood and Cambrai –

Dom Ambrose, (his name in religion), was a gifted author and poet. In later life he wrote an autobiography, detailing his experiences teaching in school, extensive pastoral work in the parishes of Somerset, Cumbria, Ealing, America – and most notably an account of his time spent in Liverpool during the Second World War, where his church (St Mary’s) was destroyed by enemy action.

The following extracts from his autobiography paint a vivid picture of late Victorian childhood and life at “The Grove” at the turn of the century. Tancred himself was silent about his ministry on the Western Front, but documents held in Downside Archives provide us with a few snapshots of the dangers he faced on a daily basis. Extracts from “Christmas in Picardy”, first printed in the Downside Review, and the Rawlinson papers –

A Victorian Childhood

“I was the thirteenth child … all the five at the end of the family were boys, and how we appreciated it! We were at boarding school together, we always had enough for a game of tennis; in childhood we cooperated in every kind of hobby and pastime.

Five o’clock was always Children’s Hour, and we assembled in a cosy room downstairs to play card games, or paste in scraps, or paint, or in general amuse ourselves happily with our elder brothers and sisters in the efficient and satisfying way of large families. The most vivid recollections of this hour are concerned with the impending removal to a bigger home, then under construction in Belsize Grove, which occurred when I was about five. How that house lingers in my memory! The cream paint, the window-

Military Aspirations

“Uncle Edgar (Pater’s brother) had run away as a young man and joined the Black Watch, refused to be bought out by his mother, and fought at El-

We also made a gatling gun (mounted on wheels) with cap pistols. We sat with this outside the oratory one morning, and my Uncle sent his dog up the stairs to attack. We let him approach and opened fire (harmlessly, of course), and he turned and ran down again. In 1915, my brother Arthur sat with his machine gun on the second morning of the Neuve Chapelle battle. With the first light of dawn the Germans counter-

During the South African War, we drilled and manoeuvred in the garden, to the annoyance of the tenant of a flat overlooking the garden. Another tenant, whose son was fighting in South Africa, sent an encouraging message. We didn’t need encouragement, needless to say, but it warmed us, and we felt quite important.

My father and the family encouraged our military aspirations. Every year we were taken to the military tournament at the Agricultural Hall, Islington, and on one occasion I was being taken behind the scenes during the interval to see the horses of the Horse Artillery. In 1917 and 1918 I was Chaplain to the 21st Divisional Artillery, and rode with the field gunners when, in the best traditions of the horse artillery, they fought from position to position after all the Infantry had been put out of action in March, 1918.”

Downside & Cambridge

“My father was urgent that a Cadet Corps should be started at our school, Downside. I left that school in 1908 well grounded in Latin and Greek, in History and in English syntax and Literature, and a working knowledge of Geography; with some taste of authority and the direction of subordinates, with a deep religious foundation and philosophy of life.”

On leaving school in 1908 Tancred entered the monastery at Downside Abbey:

“ …My journey from Paddington Station recalled the “end-

“Up to 1908 all the novices of the English Benedictine Congregation were sent to the common novitiate at Belmont… It was therefore with joy that news was received that henceforth each House would have its own novitiate. Seven of us opened the novitiate at Downside and we had to create our own traditions.”

After two years in the novitiate at Downside, Tancred went up to Cambridge to read Classics:

“Cambridge had much to give, and I received a great deal. I did well in all the papers I took. But in those days Verse Composition in Latin and Greek was compulsory, and I had not made its acquaintance at school. So I just missed a First, and that was that. I had gained, and kept, a facility and pleasure in translation, and that was a treasure for a lifetime.”

A Close Encounter with the Kaiser!

“After the Long Vacation of 1913, I was ordained subdeacon (in September) and sent off to the German monastery of Maria Laach en route for Rome. A red-

It was a successful afternoon. The Kaiser and his suite walked up and down the garden with the Abbot, and then partook of a sumptuous buffet. He presented the community with a copy of Constantine’s “Labarum” (Chi-

“Nothing can ever happen here”

At the end of a year’s study in Rome [1914], Tancred and his companions made their way home to Downside, travelling overland across Europe, taking the time to admire many fine places on the way – Assisi, Perugia, Venice, Munich.

“Our final stop was Maredsous in Belgium, a great Abbey in its own spacious grounds. Travelling sleepily in the hot train we said, “nothing can ever happen here”. But a fortnight later the German armies burnt Dinant, and the river ran with blood. We luxuriated in the halcyon calm of the Abbey, attended the Abbot’s Conference, explored the Library. We left, and a fortnight later the invading armies came.”

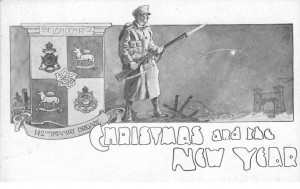

Chaplain to the Forces

In September 1915 Tancred was ordained to the priesthood and just over a year later, in October 1916, was able to perform the happy duty of marrying his younger brother Arthur to his sweetheart Dollie at the local parish church in Hampstead. Brother Edgar was best man and Richard too was home on leave. Only Alfred could not make the ceremony as he was still on duty in France.

But by April 1917 Tancred was to become the fifth brother in uniform, not carrying a rifle, but as Chaplain to the Forces (4th Class) –

“We had to hold the Hindenburg Line, with the Hun holding the same trench system on our right. The trenches were in a terrible mess, smashed up by our guns, with dead Huns sticking out of collapsed dugouts, and a litter of equipment, clothes and arms that beggars description. As we went up the Hun began strafing…”

Tancred ministered to the troops on the Western Front for a year and during that time he met up with brothers Edgar and Richard in June 1917. An account of their first unexpected meeting is given in the section of Richard’s story entitled: “In a Tent Near Mory”, (the title of a memorial poem later written by Tancred).

On September 26th 1917 Tancred was wounded during the Battle of Polygon Wood. Returning from sick leave in late October, he learned of the tragic death of his youngest brother, Richard, at Poelcapelle.

“Christmas in Picardy”

Tancred’s otherwise detailed autobiography includes no account of his experiences on the Western Front. However some time later he wrote an article for the Downside Review, “Christmas in Picardy”, in which he described the terrible conditions endured by the troops in the bitter winter of 1917. But between bombardments there were moments of high comic humour, and moments of pathos, but the festive season was eventually celebrated in traditional style, despite a few hiccups along the way:

“All through the long and severe fighting, culminating in the capture of the Passchendaele ridge, the Division had been in the line. For the Field Artillery, to whom I was attached, it was a period of continuous and considerable strain. It was with universal relief therefore, that the news of our departure south was acclaimed. On November 15th we began a leisurely journey to our new quarters at St Catherine, the northern suburb of Arras. After the constant anxiety and danger of the battle area, that week’s march, through untouched villages and country unspoiled, was a most welcome relief. There was considerable excitement also over a rumour, ever-

“All through the long and severe fighting, culminating in the capture of the Passchendaele ridge, the Division had been in the line. For the Field Artillery, to whom I was attached, it was a period of continuous and considerable strain. It was with universal relief therefore, that the news of our departure south was acclaimed. On November 15th we began a leisurely journey to our new quarters at St Catherine, the northern suburb of Arras. After the constant anxiety and danger of the battle area, that week’s march, through untouched villages and country unspoiled, was a most welcome relief. There was considerable excitement also over a rumour, ever-

By the time we had reached our destination this rumour had become certainty. New guns were picked up en route, fresh drafts of men and horses met us from time to time, stores were made up, and by the end of the month we were actually on the eve of following our mechanical transport to the Sunny South.

The Cambrai battle, however, upset all our calculations. December 1st saw us hurrying along the Arras-

The Cambrai battle, however, upset all our calculations. December 1st saw us hurrying along the Arras-

The Ammunition Column, with whom I lived, had been left to shift for themselves on the open crest of the hill overlooking Longavesnes, beside Tincourt Wood. There was no cover for the horses, and the men had only such makeshift shelter as they could improvise out of ground sheets. Our mess consisted of a large waterproof sheet stretched over four short poles, with a slightly higher pole in the centre. There were besides half-

The 24th was bitterly cold, so cold that as I said Mass in my tent there was ice in the chalice. The morning was spent in making arrangements for the morrow. In the afternoon I cycled up to Epehy, about eight miles distant, for the same purpose. The little town was of course totally wrecked. It was used as part of the reserve line and was therefore apt to become suddenly “unhealthy.”

I arrived on the heels of a gas bombardment with which the enemy ushered in the feast. There had been a number of casualties, although the men had “gone to ground.” As darkness began to fall I set out on my return journey. Halfway between Epehy and St Emilie I noticed two siege batteries in a sunken road. I had passed them, when the chance of finding some Catholics in the position made me retrace my steps. It was just as well. I had hardly entered the nearest battery when the first shell of a ” concentration shoot ” fell beside the road. It was a much-

I arrived on the heels of a gas bombardment with which the enemy ushered in the feast. There had been a number of casualties, although the men had “gone to ground.” As darkness began to fall I set out on my return journey. Halfway between Epehy and St Emilie I noticed two siege batteries in a sunken road. I had passed them, when the chance of finding some Catholics in the position made me retrace my steps. It was just as well. I had hardly entered the nearest battery when the first shell of a ” concentration shoot ” fell beside the road. It was a much-

For three-

I pushed on through the gathering darkness… As I entered on the rise out of Longavesnes I met two disconsolate figures, rushing wildly backwards and forwards in the half-

Towards midnight I made my way down to the Field Ambulance at Longavesnes. There, in a large double Nissen hut, the Senior R.C. Chaplain had arranged to have midnight Mass. The room was very prettily decorated and made an excellent chapel. During Mass the Adeste was sung, and the familiar tune “transported us from the ignorant present” and linked us up, for the moment, with the loved ones at home.

I said my first Mass after the men had gone, and then had a few hours rest before returning to the same spot for a 9 o’clock Mass. The “chapel” this time was a stable: a most appropriate setting for the Christmas morning Mass. The men present seemed to enter fully into the spirit of their surroundings. The service was over about mid-

I finally reached my unit soon after one o’clock, famished. I found the camp expecting a visit from the General, but it was postponed. The men’s dinner was being prepared in two ” field ovens ” we had built for the occasion, which meant that ours had to wait. To make matters worse the cook had so regaled himself with Christmas fare (chiefly liquid) as to be out of action for the time being.

We watched the men receive their dinner section by section. Then we set about preparing our own. But the overworked oven ” struck” absolutely. In this emergency the mess waiter laboured single-

“Heroic and Devoted Work”

After the war Fr Rawlinson compiled a history of Catholic army chaplains. Tancred wrote to him describing the impact that the Last Sacrament had on the men – both to the receiver and the general witnesses around him:

After the war Fr Rawlinson compiled a history of Catholic army chaplains. Tancred wrote to him describing the impact that the Last Sacrament had on the men – both to the receiver and the general witnesses around him:

“In the piteous work of clearing up the wreckage of battle the chaplains found to their hand a potent instrument in the Sacrament of Extreme Unction [Sacrament of the Sick]. Quick and easy to apply, this Sacrament could help men beyond the reach of human aid and put to precious use the last, often agonising moments of life. The physical alleviations which other chaplains – in default of more practical opportunities – busied themselves in applying, were useless at that stage.

But the RC chaplains, not necessarily more patient, skilful, dedicated or courageous than their companions, could awake recognition in the last glimmer of consciousness and succour both soul and body in the extreme crisis. No wonder that, as they worked in aid posts and dressing stations, they caught the glances, curious yet longing, and heard whispered words which brought home to them a realisation of the immensity of their privilege.”

When Tancred left the army in April 1918, to return to his community at Downside, Fr Rawlinson wrote to Abbot Butler that he had been an “exceptional chaplain” who had performed “heroic and devoted work”.

Post Script: “Turning Point 1918”

In April 1968 Tancred was moved to enter into correspondence with the Catholic periodical “The Tablet”, in which he took exception to views expressed there about the German Offensive, “Operation Michael” of March 1918.

Fifty years after the event, Tancred was still able to provide a detailed account of the numerous acts of courage he witnessed on the battlefield that week. And today, almost fifty years after his letter was published, we can bear witness to the outstanding loyalty and admiration he felt for the men he had worked among –

“Sir: I read with great interest and some nostalgia N.’s reminiscences of Ludendorff’s “Operation Michael.” I was then R.C. Chaplain to the 21st Divisional Artillery … We were next-

But I take exception to the statement that none of us felt that “he was a participant in a glorious feat of British arms.” Our division held, though grievously outnumbered. Nearly all the infantry were casualties or overrun in the first two days, but our guns stayed in action all that week, fighting several positions a day and “running the wheel” over any ammunition left behind. Our Lt. King survived air attack on a successful quest to salvage two forward guns then two miles behind the German front line. One battery, attacked at point blank range, pulled two guns out of the pits, broke the attack, and kept the other four guns covering the cooks, secretaries, and batmen holding the line. I met a machine gunner, sole survivor of his unit, and said: “I expect you’re glad to be out of it.” He replied: “No, I can’t wait to get back and help to finish this business off.”

At one time, till the Australians came down from the north, we had our batteries in action with no infantry in front. On the second night our wagons, going up with ammunition, found a brigadier sitting in a cane chair from the deserted village holding the line with 63 men, the remains of his brigade.

After a sleepless week we were relieved and moved north. One day we were passed by the car with Clemenceau and Foch going into Doullens to secure the unification of command. General Gough was made a scapegoat to cover up Lloyd-

Ambrose Agius, O.S.B. (21st Division Artillery) Newark, New Jersey.”

In later years

Dom Ambrose returned to Downside Abbey after the war, where he became parish priest of Radstock 1918-1932. During this time he started new parishes at Peasedown and Norton St Philip. He was often seen cycling around Somerset between his churches and contributed much to local communuity life , especially on the cricket field! He then served as Parish Priest at Whitehaven from 1932 till 1934, and St. Mary’s at Liverpool between 1934 and 1935 and again from 1939 until 1945. During the war years his church was destroyed during the Liverpool Blitz (May 1941).

In 1936 Abbot Hicks sent him to join the community at Downside’s dependent Ealing Priory. In 1929 a group of clergy and laity in Ealing had started a National Catholic Society for Animal Welfare (now Catholic Concern for Animals). Dom Ambrose joined them when he arrived at the monastery and, in 1937, he became the first editor of the society’s magazine “The Ark”, in which role he continued for 123 issues through to the 1970s, despite moves to Liverpool and USA.

Sent back to Ealing in 1945, he served as Prior for two years. In September 1947, he transferred his monastic stability to Ealing Priory on its becoming independent. As Curate in charge of the Parish, he founded the parish magazine and after a year as Junior Master at Ealing, went to Fort Augustus Abbey in Scotland. He was then sent to the United States of America for a number of years where amongst other duties he raised funds for the Abbey Building Fund. Recalled to Ealing as Cathedral Prior of Gloucester in 1968, Dom Ambrose collapsed in his room on February 17, 1978. Rushed to hospital, he died fourteen days later at 87 years of age.

Link to Whitehaven from 1932 till 1934